“His collected work runs to only 60 pages but is brimful of ideas that mathematicians today still feed off profitably”

The Guardian Newspaper – January 20th, 2012

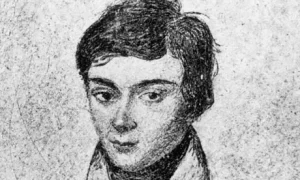

Galois was to mathematics what Arthur Rimbaud, a generation later, was to poetry. He was born in a small town south of Paris in 1811. His family were highly political, though it was a time in French history – between the revolutions of 1789 and 1830 – when to think at all was to be political. In 1829 – at the age of 18 – he published his first paper, a study of fractions. The same year, his father killed himself after a (political) row with the local priest. These were not calm people.

At 20, he joined the National Guard. The guard – a heavy-duty republican outfit – was disbanded and Galois, with several comrades, was arrested. All this might be enough to keep a young man busy, but Galois was saving the best of himself for his maths.

His work – now known as Galois Theory – is probably incomprehensible to anyone outside of the mathematics department of a university. My mathematician neighbour has tried on several evenings to explain it to me – I was graded D at O-level – and at a certain point during those evenings the theory appears before me like a beautiful, shimmering spacecraft but is gone entirely by the next morning. The general territory is algebra, specifically, algebraic solutions to polynomial equations.

In fairness, it seems very few of his contemporaries knew exactly what he was talking about, though the sharpest realised that whatever it was, it mattered. His collected work runs to only 60 pages but is brimful of ideas that mathematicians today still feed off profitably.

On 30 May 1832, the day after being released from prison for the second time, Galois fought a duel. It is not certain what it was about. Politics, perhaps, or a woman. It’s not even clear who it was against. What is known is that Galois received a ball in the abdomen and died at 10 o’clock the following morning. His last words were to his brother: “Don’t cry any more, Alfred. I need all my courage to die at 20.”

• Andrew Miller’s Pure won the 2011 Costa Novel Award.

In the same spirit…